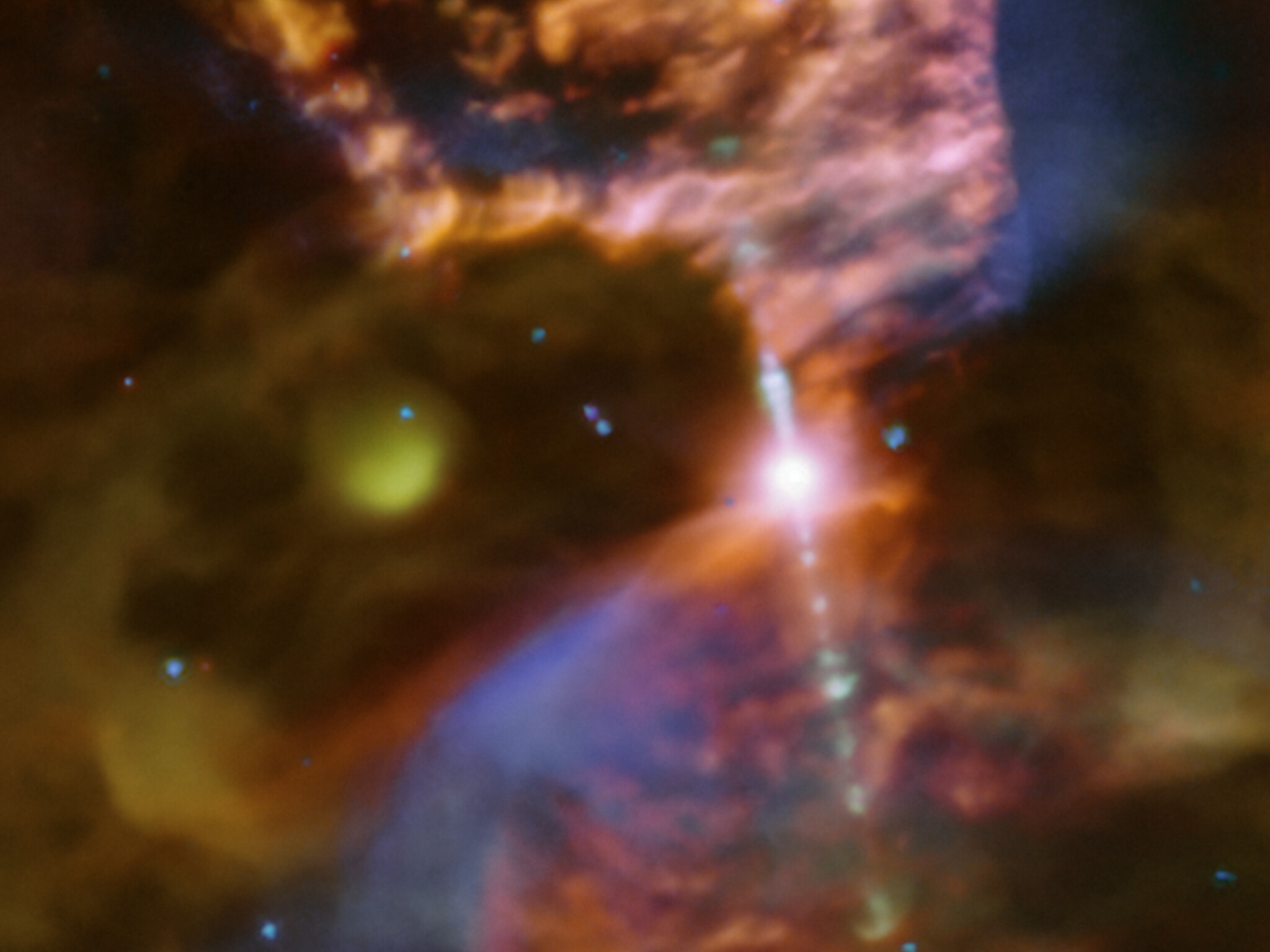

UM-led international study connects newborn star to the remnants of a supernova explosion

Discovery reveals a direct connection between stellar birth and death

Discovery reveals a direct connection between stellar birth and death

Researchers from the University of Manitoba (UM) have found an answer to a question Astrophysicists have been asking for decades. The Vela Junior supernova exploded a few thousand years ago, leaving behind a glowing cloud, but scientists couldn’t answer just how far away it was and how big the explosion was. That has changed with the discovery of an infant star.

“This is the first-ever proof linking a newborn star to the remains of a supernova,” says Safi-Harb. “It allows us to settle a decades-long debate and determine how far away Vela Junior is, how big it is, and how powerful the explosion really was.”

The study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, UM PhD candidate, Janette Suherli, and Astrophysicist Dr. Samar Safi-Harb, together with an international team of collaborators from Canada, Australia, USA, Taiwan, and Switzerland.

The research draws from MUSE data analyzed from the European Southern Observatory, using the Very Large Telescope in Chile—the world's most advanced visible-light astronomical observatory.

By analyzing gas flowing out of the infant star, the team discovered it carries the same chemical fingerprint as material from the long-dead supernova. That match confirms that the two objects are physically connected, allowing scientists to finally pin down Vela Junior’s distance.

For Suherli, the discovery highlights the ongoing cycle of stellar life and death.

“The gas we’re seeing in this young star carries the same chemical signature as the star that exploded long ago,” she says. “It’s kind of poetic, those same elements eventually made their way to Earth, and now we’re watching them help form a new star.”

The findings show that Vela Junior is larger, more energetic, and expanding faster than scientists previously believed, placing it among the more powerful supernova remnants in our galaxy.

“A star is layered, like an onion,” Safi-Harb adds. “When it explodes, those layers are scattered into space. What we’ve found is that those layers are now turning up in the jet of a baby star nearby.”

Beyond solving a long-standing astronomical puzzle, the research offers new insight into how stars evolve, how galaxies are enriched with elements, and how extreme cosmic events continue to shape the universe to this day.

The full study is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. For an image of the discovery, please refer to ESO's Picture of The Week.

If you are a journalist and want to cover this story or any other UM story, please contact mediarelations@umanitoba.ca

New study shows polar bears annually provide millions of kilograms of food, supporting a vast Arctic scavenger network.

Women are underrepresented in cardiovascular outcomes trials (CVOTs)