Just like that, he was gone.

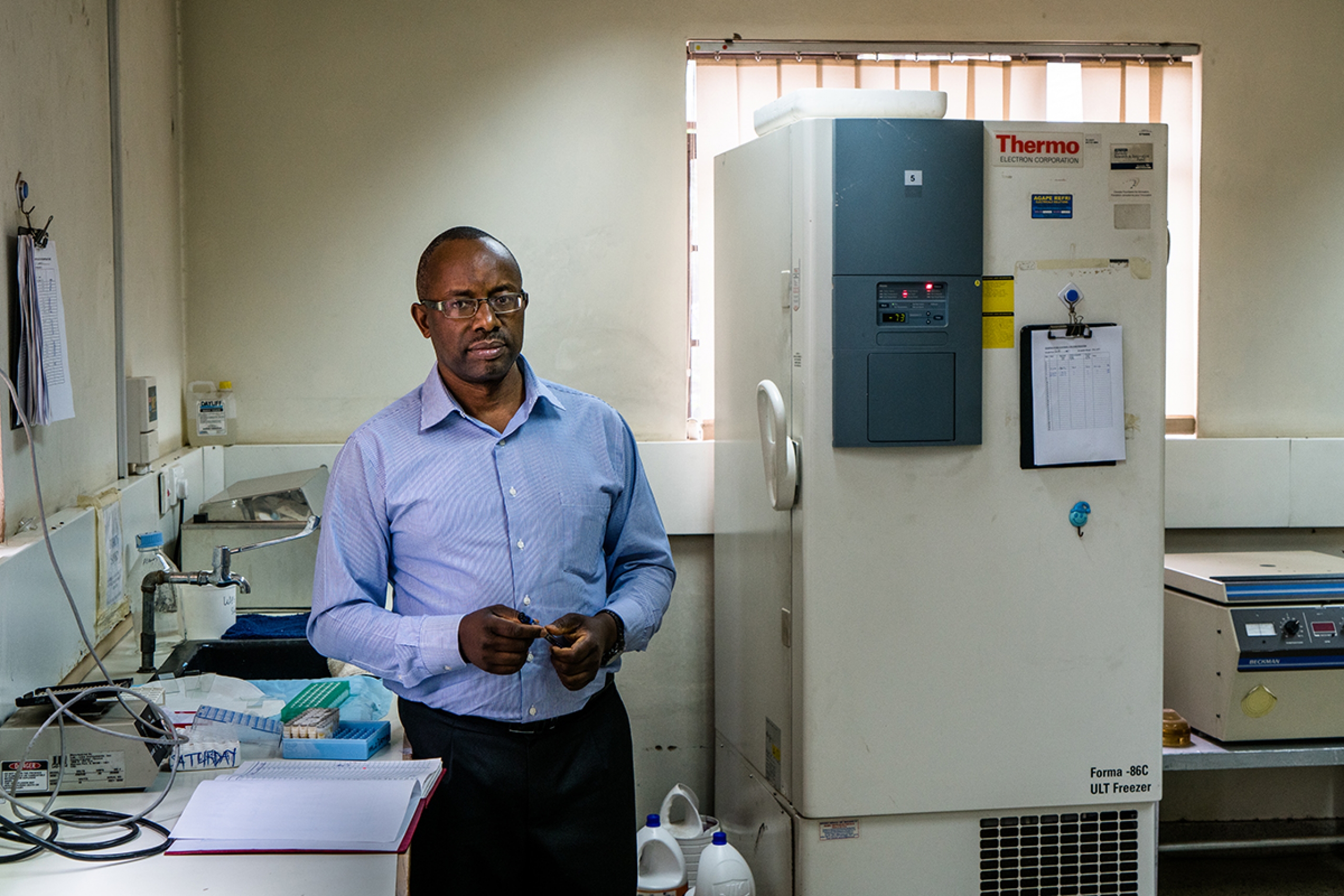

When a colleague didn’t show up for work one day, the U of M’s head of medical microbiology and infectious diseases Keith Fowke [BSc(Hons)/88, PhD/95] didn’t think too much of it until he got the phone call.

The Kenyan-born research associate he worked alongside, who trained for some time in Canada, who won awards for his keen intellect, who for years toiled away in the Nairobi lab to move forward the science to stop HIV, had fallen victim to complications from that same virus.

“I didn’t know all the time I worked with him that he was HIV-infected. He was so enthusiastic about research and its potential,” Fowke recalls. “That was quite devastating. It really brought it home. This isn’t a theoretical exercise. And even today there is still rampant stigma and discrimination and many prefer not to disclose their status.”

His colleague succumbed to a secondary infection. HIV can go for the lungs and, despite the advances in medication, a common cure remains elusive.

In the late ’80s, Fowke was a graduate student under medical microbiologist Dr. Frank Plummer [MD/76] when they made a major discovery that significantly advanced the international pursuit of a vaccine. They uncovered that some Kenyan women, all of them sex workers, were somehow immune to HIV despite having been exposed to the virus up to 2,000 times.

Fowke was on the balcony of his Nairobi apartment crunching reams of data he brought home from the lab and couldn’t believe it. “I remember grabbing the phone and calling Frank and saying, ‘Our theory was actually right.’”

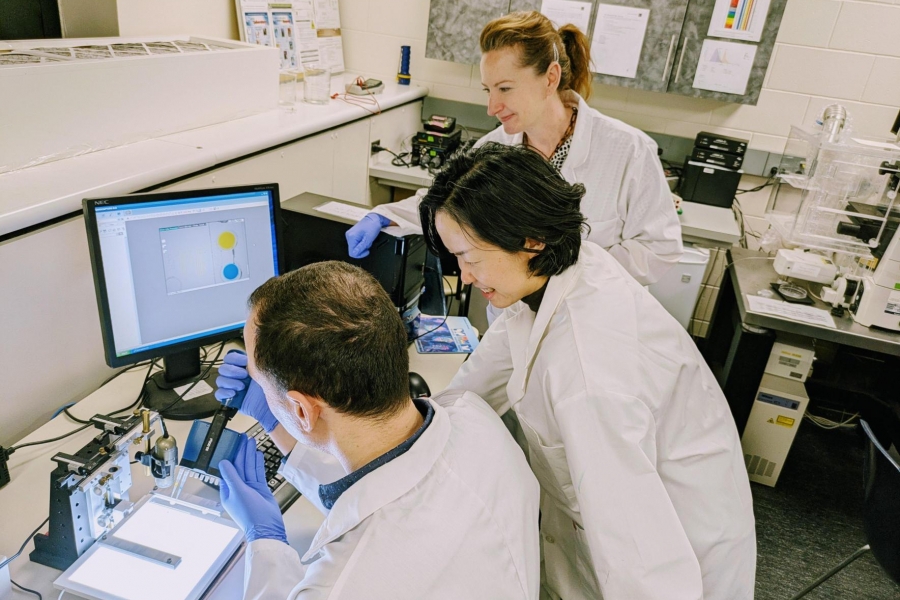

The women had natural immunity; their healthy cells were killing the HIV, prompting scientists worldwide—from Sweden to Israel—to explore the phenomenon in others, including heterosexual partners of those infected, gay men and haemophiliacs.

Fowke now knows that the immune cells of the women in the study with this natural resistance are calm or less active and overexpress a protective protein. They know resistance can drop when sex workers take a break, and can run in families.

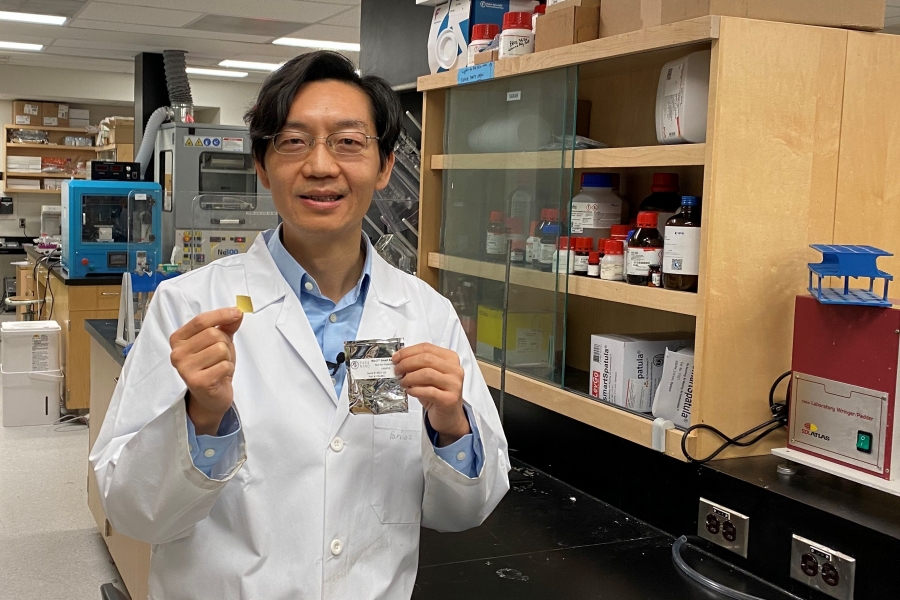

He is cautiously optimistic the latest breakthrough might come in the form of a simple pain pill. While substantiating the findings is ongoing, he and his team so far have learned that by reducing the presence of the type of cell that HIV targets in the genital tract, they can reduce the chance of infection. Acetylsalicylic acid (better known as Aspirin), his latest research shows, is a way to keep these cells to a minimum. The team’s initial findings show the pill can shrink the number of these cells by 35 per cent. “Then, when HIV does show up, there’s no way for it to get a foothold and initiate an infection,” Fowke says.