By Katie Chalmers-Brooks

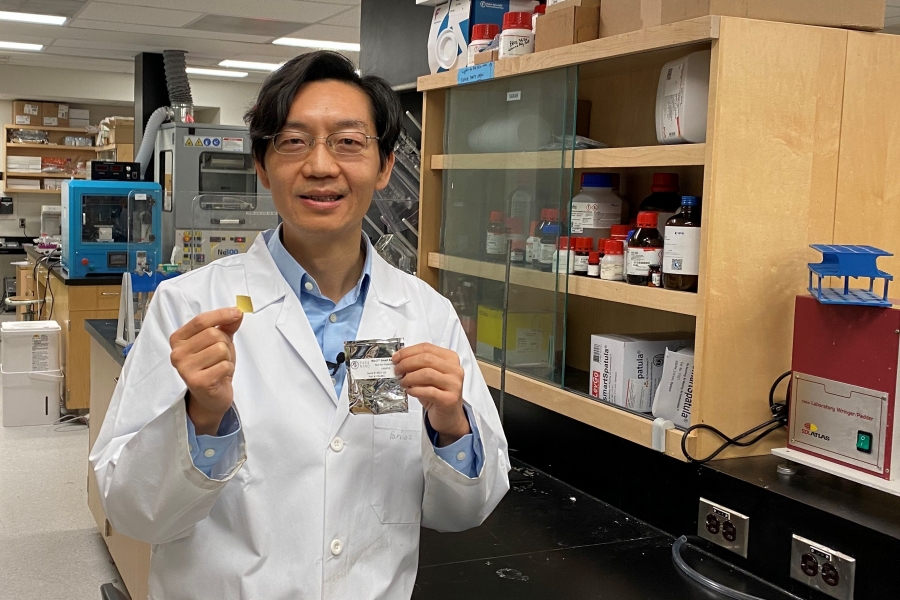

The little girl with the pink glasses and blue sweatshirt smiles back from a photo on the wall. It’s hung in Tamra Werbowetski-Ogilvie’s sixth-floor office, overlooking the treetops of the neighbourhood surrounding UM’s Bannatyne campus.

Alongside the framed photo are images of her own two children, including her daughter. She’s around the same age as this tween who was undergoing cancer treatment and who was connected to a foundation that funded Werbowetski-Ogilvie’s work in pediatric brain tumours—the deadliest of childhood cancers.

The Rady Faculty of Health Sciences researcher recalls chatting with the inquisitive girl on a Zoom call a year ago.

“Those are emotional meetings, you know? And I can’t get through them without crying. She was so thankful when I met her and just so happy that people were doing work,” says Werbowetski-Ogilvie. “It hits you. See? Already, I'm getting emotional.”

That’s why she opted for life as a stem cell biologist instead of a physician. Pediatric brain cancer became an obvious choice; it’s a discipline starving for discovery. This cancer is surprisingly rare in kids; it’s only been in the last decade that research in this specialized field has gained momentum, with advances in gene sequencing technology.

But still, children’s cancers in general are “ridiculously underfunded,” Werbowetski-Ogilvie is quick to point out.

“In the States, they account for less than four per cent of all funded research in cancer. And it’s the same everywhere.”

Roughly 1,000 kids are diagnosed with cancer in Canada every year, including about 50 in Manitoba. Around 10 of these children will learn they have a malignant tumour in their still-developing brain. A few of them will be diagnosed with a medulloblastoma tumour—the type Werbowetski-Ogilvie investigates.

"Parents don’t care how rare it is. They want to look for better treatments."

She’s saying this just weeks before the prestigious journal Nature publishes what is possibly her team’s biggest findings to date. With collaborators in Toronto, Seattle and Tokyo, they pinpointed how and where aggressive types of medulloblastoma first appear—in pre-malignant form—during a child’s brain development, while still in the womb. Kids aren’t usually diagnosed with this type of tumour, known as group 4, until age seven, which suggests there’s a window of several years to prevent the cancer from ever happening.

Until now, group 4 tumours were the least understood, yet they require some of the most intense treatment. Up to 40 per cent of kids don’t survive.

With new clarity of which genes go awry and grow into tumours, clinicians could potentially detect these problematic cells before they turn into cancer—it’s the first time scientists have suggested medulloblastoma is preventable. They can also now develop better human cell models to test potential drugs to slow or stop its spread.

“With better models, we’ll actually be able to make some headway,” says Werbowetski-Ogilvie.

Brain cancer, she reiterates, doesn’t always get its moment in the spotlight. Greater attention tends to go toward unravelling the mysteries of leukemia, which affects the blood and is the most common cancer among children.

“In the leukemias it seems that there’s been better strides made in terms of survival rates. Whereas with brain tumours—especially for these really, really bad cases—current therapies are really not extending life beyond an extra couple of months and are so toxic,” she says. “We need to do better for brain tumours. And I think we are definitely moving in that direction.”

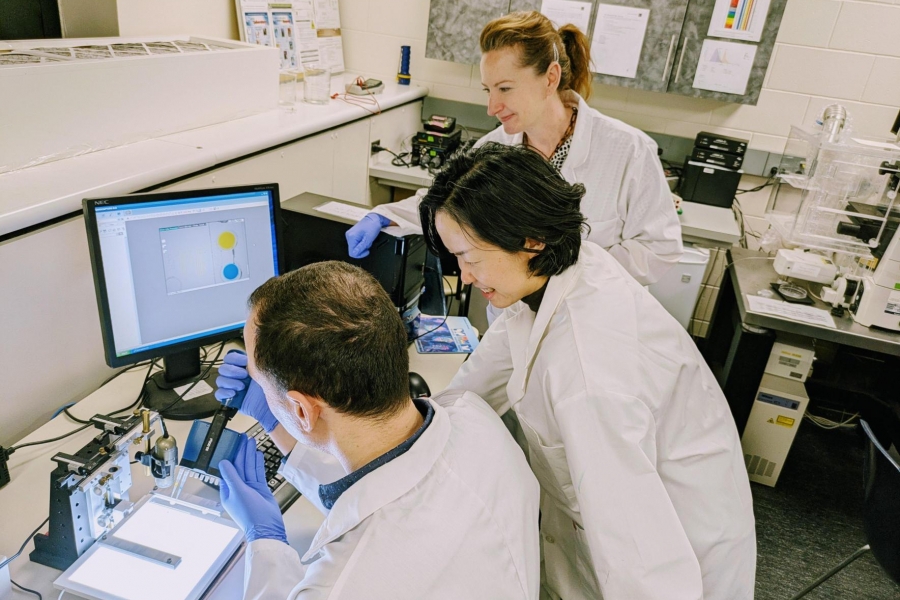

The search for new treatments finds fuel in cancer stem cell biology, where scientists identify a tumour’s “cellular fingerprint.”

“We’re looking for the proteins on the surface of a cell as well as inside the cell that make those tumours unique,” says Werbowetski-Ogilvie. “And then we look for drugs that will target that unique signature.” That way oncologists can go after diseased cells while leaving surrounding healthy cells intact.