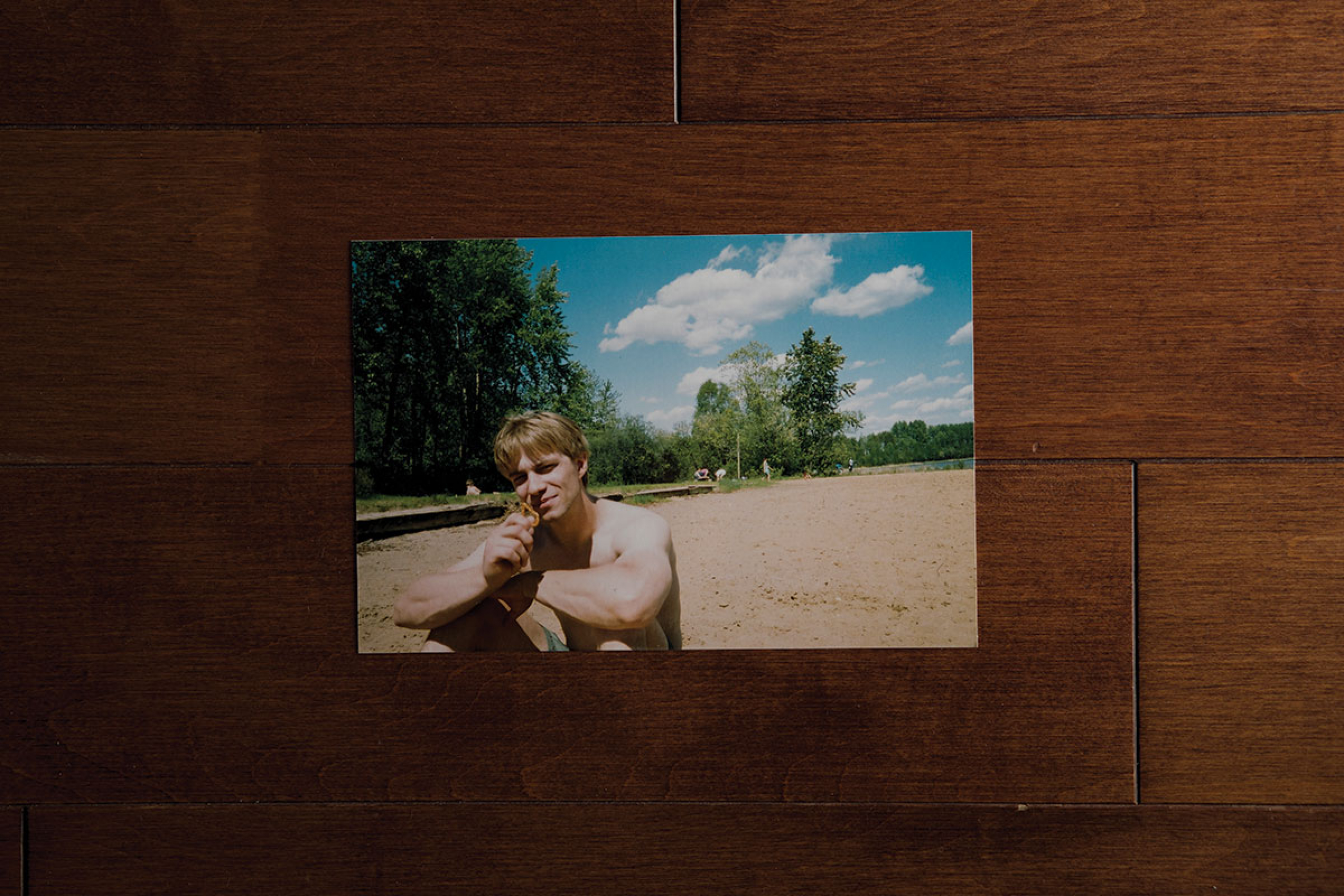

Nine months after the fire, Beach rolled over for the first time. He had lost 63 pounds and at six-foot-two was down to 112. The scar tissue had built up on his ligaments and tendons, and his muscles were wasting away with atrophy. The movement was small but it felt like a big win that came just in time. After the fire, he was angry, depressed, suicidal; now he wanted to see what else he could do for himself.

With progress comes greater survival rates, which means more people living with the long-term consequences of burn injuries like disability, financial problems and chronic pain. Trauma survivors are at least four times more likely to take their own life, Logsetty and Sareen revealed in a 2014 study. They’ve since discovered they’re also twice as likely to have depression, anxiety or substance-abuse issues.

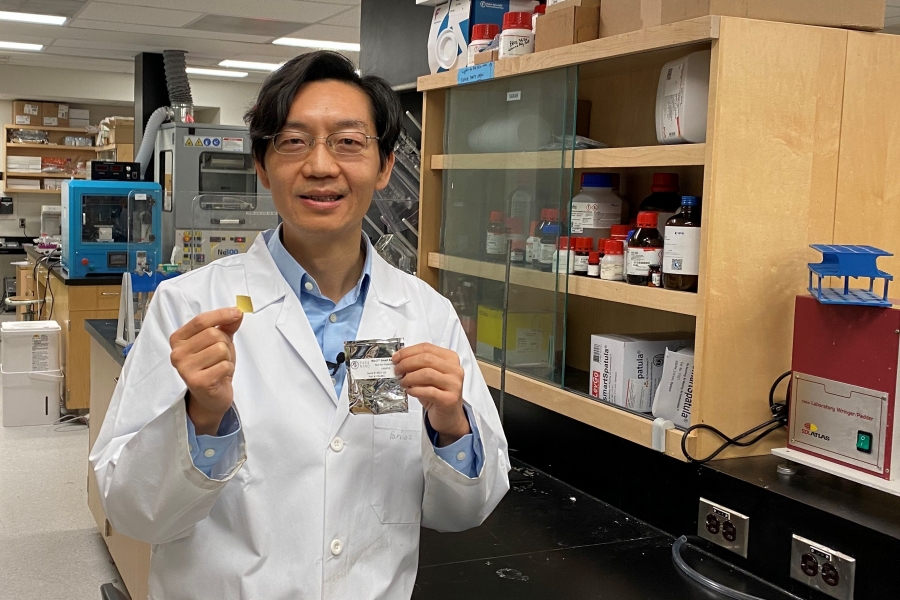

Logsetty says patients often tell him they don’t want to go on. He helps them reintegrate with the life they once had, as much as possible. “It’s not, I fixed your hernia, your sutures are out, you can call me if you have a problem. There is a continuity of care we don’t see in most other surgery.”

That’s why he’s made this his life’s work. One patient describes Logsetty as “the most caring and considerate doctor I have ever met;” another says he “created a place of love in the burn unit.”

The only burn expert between Edmonton and Toronto, he makes himself available 24-7 to residents and nurses, even when not officially on call. “The standard of care I try to hold myself to—and teach my students—is What would you expect for you or your loved one?” says the father of two kids (under age seven), and husband to epidemiologist Rae Spiwak [BA(Adv)/00, MSc/04, PhD/17], who also studies mental-health issues in trauma patients.

“The biggest thing I’ve learned is that life can change in an instant.”

This summer, Logsetty spoke at Winnipeg’s inaugural Face Equality Awareness event for people living with facial differences. “It’s important,” he adds, “to help people understand that, although the outside of somebody might have changed, the inside is still the same—part of what our team does really well is help burn survivors come to that understanding themselves.”

It was Beach’s wife who held up the mirror for him the first time, only once he’d consulted with a psychologist. He couldn’t bring himself to look beyond his nose, with its missing lobes and exposed bridge. Gone was the dimpled grin of a guy who was always the life of the party.

Now, if kids stare at the grocery store, he’ll engage with a smile and a wave. Often, they think he’s just really old—a grandpa, not a father, to his kids, he says. When adults approach, which he’s totally fine with, it’s always the same question: Can I ask what happened?

Beach doesn’t have photos of what he used to look like up in his house, only because “they’re not picture people.” And no longer does he appear as his former self in his dreams.

“I’m extremely proud of who I am,” Beach says.

He’s a motivational speaker who finds fulfillment in trying to create positive change in the workplace, who’s spoken to Winnipeg workers about putting safety before money and supervisors’ demands. But his life isn’t without ongoing challenges.

He has nerve damage and reduced mobility in his joints.

(He says he has the equivalent of seven-and-a-half fingers, since doctors had to amputate portions, up until they found blood flow.) And with some stubborn wounds that won’t heal, he regularly gets blood infections—20 in the last 10 years. Nonetheless, he renovated his basement and next, he’ll build a fence.

With burn survivors like Beach, Logsetty notes, “The scar doesn’t define them. They define themselves.”

In a recent Facebook post, he signed off “one tough son-of-a Beach.”

“You want to be the person you used to be,” Beach says, “but now you have a different body to do it with.”

He returned—just once—to the site where it happened. Where a new house now stands.

“I had to see it.”